By S.K. Moore, PhD.

– – –

This post is the second installation of a two-part series on Michel de Peyret’s experiences with Religious Leader Engagement in Kosovo. Read the first installation here for a fuller grasp of the context and the characters in this account.

Reframing the Mission: Religious Leader Engagement

Before de Peyret redeployed to France, the soon-to-be new KFOR Commander arrived for a reconnaissance visit—Lieutenant-General Yves de Kermabon, Commander of the Army (French Defence Forces). He soon learned of the chaplain’s humanitarian activities and the resulting improved relations with the Serbian Orthodox community following the earlier rioting. At de Kermabon’s, de Peyret was extended for a second tour and elevated to the position of Formation Chaplain.

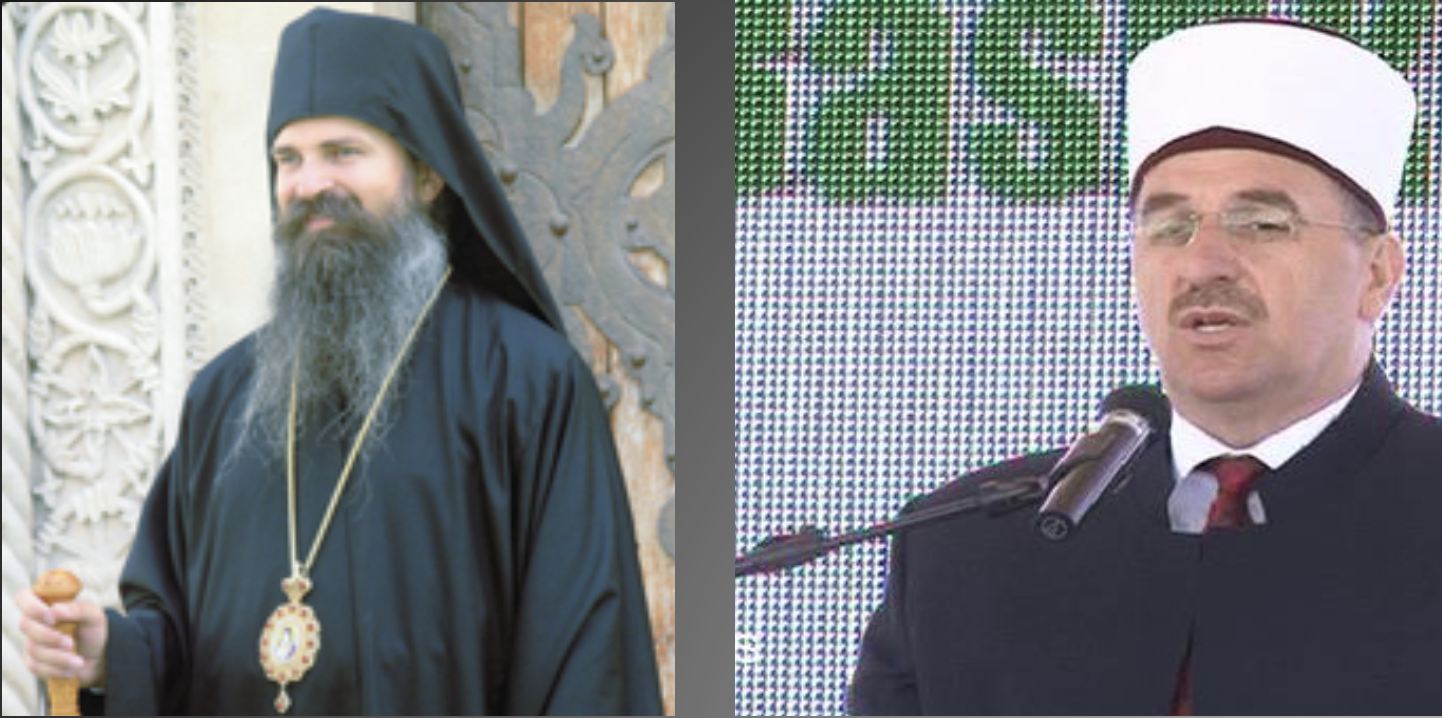

Upon his arrival, the Commander briefed de Peyret on the specifics of his new duties. Cognizant of de Peyret’s previous peacebuilding endeavors among the Orthodox community, he now looked to the chaplain to replicate similar peacebuilding initiatives among the religious communities for the whole of Kosovo. This meant establishing good relations with the leadership of all three faith traditions: Grand Mufti Ternava (Albanian Muslim), Mgr Teodosije (Serbian Orthodox Bishop), and Mgr Sopi (Albanian Roman Catholic Bishop). Having previously created a good rapport with the Orthodox Bishop, it remained for de Peyret to gain the confidence of the Roman Catholic Bishop and, more strategically, Grand Mufti Ternava.

Bridging the chasm between Serbian and Albanian religious communities created by the recent violence meant initiating a process of gradual rapprochement—an incremental approach of successive steps to increased engagement. Establishing dialogue among Kosovo’s religious leaders was largely dependent upon support from the Albanian Muslim community.

It seemed more probable to de Peyret that Grand Mufti Ternava would consider establishing more open channels of communication if rapport with both the Orthodox and Roman Catholic Bishops had already begun and was, indeed, ongoing.

A devout Roman Catholic, General de Kermabon recognized the importance of worship and the value of moving among the people of local civilian parishes as opposed to remaining entirely within the confines of the KFOR Headquarters for mass with the troops. Mgr Marco Sopi—Bishop of Prizren, a diocese corresponding geographically to the territory of Kosovo—warmed to a visit from de Peyret upon learning that the Commander had begun worshiping with local parishes, offering a short prayer during the service followed by a brief address to the people.

With positive inroads established among the Roman Catholic community, de Peyret turned his energies to the Serbian Orthodox. Mgr Teodosije readily recalled de Peyret from the recent restoration of the Devič Monastery by the French—there was an open door. As a gesture of fraternity and goodwill, the Bishop extended an invitation to celebrate Easter with the Orthodox community at his Monastery at Decani. Then, hearing of the established rapport with Mgrs. Teodosije and Sopi, in a spirit of hospitality, Grand Mufti Ternava greeted the KFOR chaplain cordially as well.

Breaking Bread Together: Apology and Acknowledgement

When it emerged that no historical account existed in Kosovo of Muslim, Orthodox, and Roman Catholic religious leaders having ever come together for dialogue, the possibility of a shared meal began to germinate. It was determined that the ‘neutral’ ground of KFOR Headquarters would be the more appropriate genre to host the luncheon. In this meal, de Peyret saw an opportunity to seed reconciliation—to transcend alienation, initiate a new narrative of cooperation, and begin the healing of memory for these communities. Enough trust had been built to bring the three leaders together for a shared luncheon with the Commander of KFOR.

Invitations were extended, starting with President of the Islamic Community of Kosovo, Grand Mufti Ternava (Muslim); Serbian Orthodox Bishop, Mgr Teodosije (Orthodox); and, finally, Roman Catholic Bishop, Mgr Marc Sopi. The understanding was that there would be no publicity—key to achieving cooperation, as the sensibilities surrounding such an event potentially bore consequences within each leader’s respective community. All three religious authorities agreed to attend, each accompanied by an ‘assistant.’

Mgr Teodosije arrived an hour late, an inauspicious beginning to what was already a tenuous meeting. Once there, he offered his apologies for his tardiness, explaining that he had just returned from Belgrade, which made it difficult to arrive at the agreed upon hour.

At the outset, the atmosphere was quite stilted, with no one wanting to be the first to speak. Benefiting from the silence, Mgr Teodosije rose, requesting the floor. There, solemnly, before the assembled, he addressed Grand Mufti Ternava, declaring that he was sorry for any wrong his people may have caused the Albanian community. The Bishop then explained that the reason for his trip to Belgrade was to consult with his fellow Serbian Orthodox Bishops regarding the meal they were now sharing and what he proposed to say. After offering unanimous approval, the Orthodox Bishops further requested him to offer the same sentiments on their behalf as well.

The intensity of the moment was palpable in the small dining room—total silence. The Grand Mufti stood slowly, visibly moved by what he had just heard. Grasping the Bishop’s hand in his, he presented him with his business card, a symbol of good manners and a gesture of goodwill in Kosovo. He then earnestly exclaimed that if there were ever anything that he could do for him, it would give him great pleasure to be of assistance. No one moved, awestruck by what they had just witnessed—an offered apology and an acknowledgement of the goodwill behind such a gesture—something almost unimaginable in a region where the amalgam of religion and nationalism has historically contributed to the complexity of relations.

The following day, Lieutenant General de Kermabon entertained the highest representatives of the UN Mission in Kosovo for a meeting. Innocently, the Commander inquired if they had any idea who he had entertained for lunch the previous day. Upon learning the names of his guests, the two higher representatives of the political powers were without words. It seemed impossible to them that these three leading religious figures of Kosovo would ever agree to sit at the same table, much less talk in terms of apology. The following week, the three religious leaders representing Islam, Serbian Orthodoxy, and Roman Catholicism in Kosovo came together for a second time during the summer of 2005 at KFOR Headquarters in Pristina with the political dignitaries … and the press. The three religious leaders of Kosovo voiced their confidence that meetings like this one would continue in the future, facilitating mutual recognition and restoring confidence among their communities.

Tentative Beginnings: Lasting Change

Salient to this account is the recognition of the moral authority that religious leaders enjoy among the people as well as with political leaders. As middle-range actors, they move with relative ease between the grassroots and the upper echelons of government. In this instance in Kosovo, facilitated by the efforts of Padre Michel de Peyret, the religious leaders of all three major faith groups came together for the greater good of all their peoples. Some of the personalities may have changed over the years, but the goodwill established during that initial encounter has served as the bedrock for continuing relations to this day, a testimony of fraternity and solidarity before the people of Kosovo. Religious Leader Engagement has become a strategic operational capability of military chaplains, the principles of which easily crosspollinate within civilian endeavors of like kind.

– – –

S.K. (Steve) Moore, PhD has been a Padre in the Canadian Armed Forces for 22 years, with operational tours to Bosnia during the war (92-93), Haiti (97-98) and doctoral research in Kandahar, Afghanistan (2006). His post-doctoral work led to the chaplain operational capability, Religious Leader Engagement (RLE), now being integrated into military training. He has advanced RLE within NATO and the Commonwealth, increasingly assimilating a whole-of-government application—concepts now being adapted to the civilian sector. His publications include “Military Chaplains as Agents of Peace: Religious Leader Engagement in Conflict and Post-conflict Environments” (Rowman & Littlefield, 2013) and “Religious Leader Engagement as an Aspect of Irregular Warfare: the dénouement of a chaplain operational capability” (CANSOFCOM, 2020).