By Steven K. Moore, PhD.

Originally published in the Broadview – Magazine of the United Church of Canada.

– – –

In May 2023, I was a panelist at the Taiwan Ecumenical Forum, a two-day annual event hosted by the Presbyterian Church in Taiwan (PCT). My experience of war and current research for the Canadian Department of National Defence on peacebuilding and contemporary conflict lent itself to the forum’s theme, which examined the corrosive effects of fake news on social media platforms. These threats are all too real for the Taiwanese, who live in the shadow of an increasingly aggressive China. For them, fake news is cognitive warfare.

One of the forum organizers, Anita Chang, explained that in Taiwan, the forms of disinformation are manifold, all aiming to polarize society, stir distrust against the government or corrupt democracy. Last July, fake meeting minutes alleged that the Taiwanese government was developing biological weapons to use against the Chinese. A few months later, fake news reports on the shortage of essentials like tissues and eggs led to panic buying. According to the Taiwanese, the Chinese government has been known to flood websites with this type of false information to sow confusion among the people — in effect, undermining democracy.

Many Taiwanese, regardless of their faith tradition, feel threatened by China. Buddhists and Taoists — both majority religions in Taiwan — have voiced opinions regarding the country’s geopolitical situation, but many decline to engage in political discussions for fear of repercussions. The threat is much more palpable for Taiwanese Christians.

Presbyterians are targeted due to their long history of aiding the democratization of Taiwan and their strong support for the sovereignty of the country. A few years ago, the Chinese posted on Facebook that the PCT had cut ties with the ruling Democratic Progressive Party because Taiwan’s president had passed the law legalizing same-sex marriage. The PCT clarified that this was false. In 2019, the Chinese state-owned media outlet Wen Wei Po reported that Chinese authorities temporarily blocked access to the PCT website for internet users in Hong Kong in retaliation for the church’s support of the pro-democracy movement. Never had I felt so complacent as a Christian from the West, so removed from the reality of what believers confront in other parts of the world — humbled by the vibrancy of their faith and honoured to be among them.

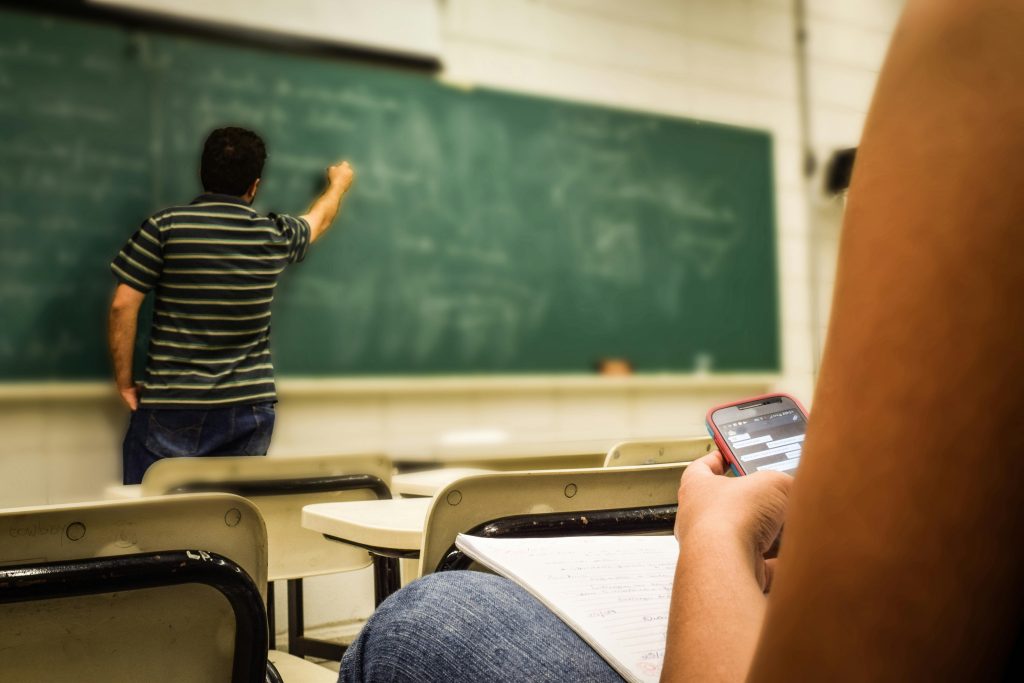

When it was my turn to speak, I talked about a country that was doing a remarkable job in combating fake news: Finland. According to research conducted by the Media Literacy Index, produced by the Open Society Institute in Bulgaria, Finland has led Europe for the past six years in fighting disinformation and misinformation on social media among their youth. In 2016, the country introduced what has become a multi-platform information literacy program into its national education curriculum. Students of all ages are taught the ins and outs of fake news — an increasingly important lesson, since they are subjected to disinformation on social media 24/7.

At the primary level, educators in Finland use fairy tales and fables — like the wily fox who always cheats the other animals with his sly words — as building blocks. As students move through the early grades, math lessons begin to include examples of how easy it is to lie with statistics. In art classes, pupils see how an image’s meaning can be manipulated. In history, they analyze past propaganda campaigns. And in language classes, teachers explore the many ways in which words can be used to confuse, mislead and deceive.

When they reach secondary school, exercises include examining claims found in YouTube videos and social media posts, comparing media bias in an array of clickbait-style articles, and probing how misinformation preys on the emotions of readers. Students even get to try their hand at writing fake news stories themselves. In 2019, long before AI became a hot-button topic, Finland was already talking to young people about it.

A 2022 report, also conducted by the Open Society Institute, looked at 41 European countries to determine their media literacy. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Finland ranked first. The report credited “widespread critical thinking skills among the Finnish population and a coherent government response” as the key reasons the country’s residents are able to resist fake news campaigns.

According to a 2019 CNN report, representatives from many other European countries and as far away as Singapore have travelled to Finland to learn about its approach and to copy its blueprint. At the conclusion of my presentation, the first question posed was: “Will Finland share its curriculum?”

In Canada, we share similar challenges with dis/misinformation. Legitimate journalists and media networks are inundated with accusations of reporting mistruths, while social media bots have targeted Canadian members of Parliament. As a result, many people are confused as to what to actually believe. Our recent experience with vaccines during the pandemic, where false claims undermined health authorities’ efforts to get all Canadians vaccinated against the virus, is just one example of how divisive the misuse of social media can be.

While most of Canada’s provincial curricula do cover digital literacy and online safety — including how to evaluate sources — Finland places a much greater emphasis on preparing its youth to navigate the rapidly evolving world of disinformation. The Finnish strategy needs to be considered in Canada, too.

Just like the faith groups’ forum in Taiwan, I believe an alliance could be forged among Canadian faith groups who share similar concerns — a coalition of the willing to buttress our educational system, as the Finns have. The United Church of Canada should help lead the way.

– – –

Rev. S.K. (Steve) Moore, PhD has been a Padre in the Canadian Armed Forces for 22 years, with operational tours to Bosnia during the war (92-93), Haiti (97-98) and doctoral research in Kandahar, Afghanistan (2006). His post-doctoral work led to the chaplain operational capability, Religious Leader Engagement (RLE), now being integrated into military training. He has advanced RLE within NATO and the Commonwealth, increasingly assimilating a whole-of-government application—concepts now being adapted to the civilian sector. His publications include “Military Chaplains as Agents of Peace: Religious Leader Engagement in Conflict and Post-conflict Environments” (Rowman & Littlefield, 2013) and “Religious Leader Engagement as an Aspect of Irregular Warfare: the dénouement of a chaplain operational capability” (CANSOFCOM, 2020).