By Doug Koop

– – –

David Foster Wallace began a memorable commencement address with a story about two young fish swimming along, and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, “Morning, boys, how’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, “What the hell is water?”

Inhabitants of any environment take many things for granted. Each of us lives in a place and time to which we naturally adjust. While we may not like everything about our circumstances and will do what we can to make them better, there are aspects of our ordinary that are very different from the assumptions of people who live in different cultures, or from those who lived in different eras. Practices and ideas are different. Values vary. Priorities change.

History is not kind to many of our forebears. We look back askance at the idiocies of those who came before, be it blood-letting or virgin sacrifice. And it’s not like we have to go back very far. Magazine ads from the 1950s, for example, portray doctors recommending cigarettes and house wives attempting to please their husbands in ways that now make us cringe. The propriety of today is the bane of tomorrow.

Yet we are hardly aware of much of this. We imbibe the ethos of our surroundings with as much attention as fish give to the water in which they swim. Which makes me wonder how different I’d be if I’d been born to different parents in a different place at a different time. Would the truths I claim and the values I espouse shine through, or would I be one of the jerks, a person whose behaviours I now disavow or disdain?

What if?

So let me take this further and more personal. What if I’d been born the son of a public executioner in some medieval fiefdom where overlords exploited the largely ignorant and superstitious masses; where religious leaders employed harsh measures to guard the faith from heresies? Would I have entered the family business with a sense of righteous authority? Would I have warmed to the task at hand and cut short the lives of my fellow villagers when their temperament, passions, beliefs or circumstances placed them in my lawful grasp? Would I have been cruel, or merciful, in the execution of my duties?

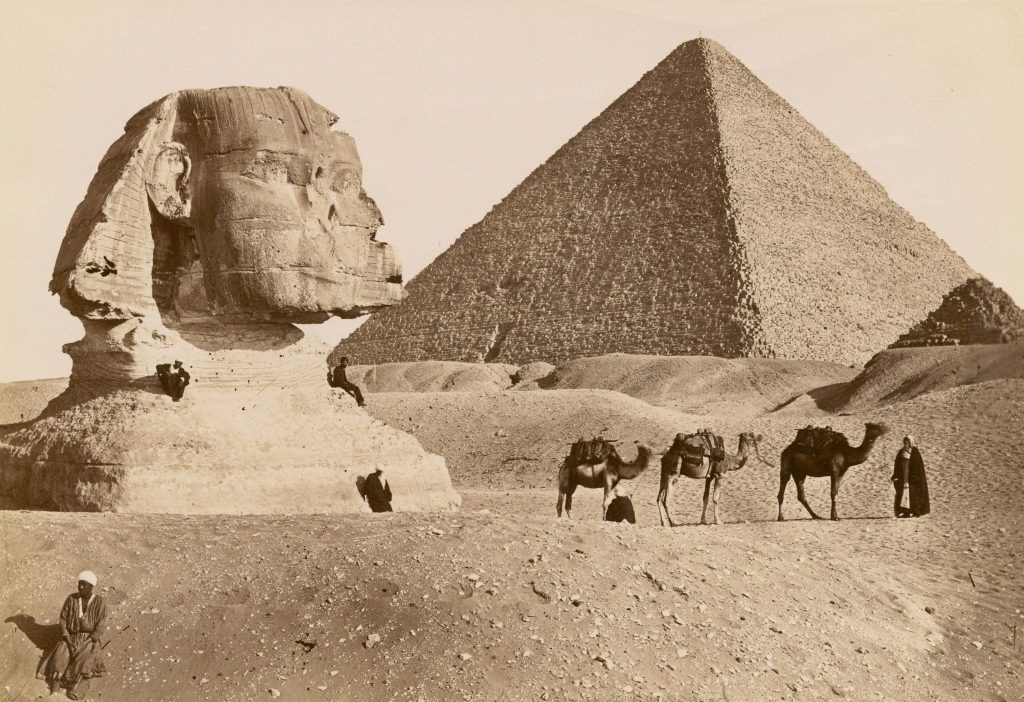

Or say I’d served as a soldier in ancient Pharaoh’s army. It could have been me striding into the strangely dry sea pursuing Moses’ tribe of frightened refugees in their desperate, uncharted bid for freedom. Then it would be me feeling the mud thickening at my ankle, glimpsing the return of a rushing tide, in an awful instant apprehending the horror of a drowning death. And there it would end, with scarcely a trace of my existence, and that a mere footnote in the history of the damned.

What if in the days of Israel’s judges I’d been an ordinary Philistine, happy for a feast day in Dagon’s temple, pleased to be part of the revelry, enlivened by the sight of a formerly fearsome (now shamed and blinded) enemy bound in chains and subjected to our jeers? My victory then would be short-lived for when Samson laid hold of the pillars and with a primal roar hushed our merriment, I perished with my friends beneath the crushing stone.

The possibilities for moral disaster are ever available. Put me in Nazi Germany, a working man industrious for family and country. If I’d inhaled Hitler in his prime, strutted in the flag-bedecked square and lustily joined in the chorus of heils, would I forever be a fiend to history, an agent of Holocaust?

As a child of Dixie, it could be me wielding a club on a Bloody Sunday, me standing on the wrong side of the bridge, on the wrong side of history. And it could just as easily be me dwelling in some dusty Mideast outpost, an ardent devout with righteous zeal and holy armoury stockpiled to consign blasphemers to oblivion. Heaven forbid.

What now?

Is it only time, distance, and circumstance that separate me from actions I currently deplore? Or could there be some deviltry lurking yet within, a seed ready in right conditions to ripen into cruelty and worse? I wonder if what I don’t know about myself or my world might impel me to commit acts I now consider heinous, or what lethal actions of my everyday are already causing harm—the dangers in the “water” I have yet to apprehend.

There seem to me more questions than answers. We all are steeped in the monoxide of our cultures, invisible toxins that destroy nonetheless—the plastics of our convenience that amass to strangle the ocean. Issues of environmental degradation are an area where my complicity is haunting clear. Yet what else might in the innocence of my daily living cause greater harms ahead? Will ignorance provide any excuse against the judgments of God, or history?

My life is unfolding in a mostly privileged manner. I’m gainfully employed, reasonably educated, ever engaged in an unfolding array of personal and professional mini-dramas— things that matter a lot in the moment yet endure but for a season.

I know more than I can bear about the larger dramas playing out in other places, where the endless cycles of strife disempower and brutalize whole populations, and in many other places where the arc of human kindness is tugged against the good. And always people respond with blame, pointing fingers and shouting their certainties across the divide. To no positive avail, of course. Conflict. The suffering that follows claims the powerless as its first victim. As an African proverb observes, “where elephants fight, the grass gets hurt.”

I am neither grass nor elephant, but something in-between. My compassion is touched by knowledge of travails both near to home and far abroad. My heart responds and (occasionally) my wallet opens, small energies minuscule in the context of the problems.

More common are the times I settle for a second-rate response, when it’s obvious (at least to me) there’s more within my means to do—some panhandler to engage but for a minute, or an extra task to finish before the ending of the day. I am aware (grudgingly) of countless times when an opportunity for a gentle word or deed is lost in the hurry of my moment, where the generousity of my spirit shrivels, where some persistent desire inclines me to disconnect from those around, to give short shrift to my better nature.

In myriad wee ways I nudge the cultural barometer towards isolation, away from the reconciliation we so sorely need.

I’ve tried to take to heart Richard Rohr’s telling observation that the best rebuke of the bad is the practice of the better. Perhaps I’ve settled for the practice of the decent. Overall I’m on the side of the angels, but far, far away from the first ranks. I’m in the borderlands here, the contested areas, the realm of the secular, living with sorrows and joys and all that life serves up. And I know I’m not alone. This is the ordinary human condition. It’s the days of our lives.

What hope?

Many of us find our coping strategies. Mine collapse into a long list of activities such as walking, praying, crying, reading, writing, and imbibing. I yearn to see beyond the present circumstances to some solace that awaits. Since I was young the ferment in my soul has sought traces of the transcendent, discovering it in moments of childhood holy devotion, in the lilt of adolescent poetry, in long searching walks and ongoing rumination.

Family circle hymn singing recalls cozy domesticity, lap time suffused with pleasant tones, moments providing an interlude where heaven and earth come strangely together, a brief fusion of material and divine. I liked that.

My sense of the unknown beyond—God territory, if you will—has overall been optimistic. I’m inclined to believe it will all be well in the end. Angry God has at times loomed with finger-wagging fierceness, a harping irritation that never fully goes away. (What if some hell awaits?) The lingering effects of those fears now niggles my conscience towards being more loving to both God and neighbour. While my driven ego often rebels, I’m happy anytime to shed a rule-bound, record-keeping sense of the Unity underlying all existence. The chief article of my faith—religious and intrinsic—is that love is the absolute foundation, and I hope to embody this spirit of love in the activities of my daily living.

Personally, it’s impossible for me to confine the scope of the possibilities to the realm of the material. Many people, I know, simply and truly believe that once breath and blood goes out of the body, a particular existence is complete. Over. Done, until the decay returns its nutrients to the firmament and new life keeps reappearing. Cycles. Seasons. Episodes. Nothing complete in itself. These are not uncomfortable beliefs. Yet my inner compass intuitively pulls towards a different North Star. For me the firmament harbours mysteries of the ultimate.

Any direction I look—inward, outward or upward—leads to larger questions. There is no end to the possibilities of learning to know anything better, no end to our potential to savour each moment for richer experience. I can discover this every day in my relations with my neighbours and my world, in the depths of my own conscious interactions and awakenings, in the respect I accord to the ever-unfolding Mystery whose essential unity I long to apprehend.

Glimpses come my way, oh yes. But I want more. More face time. More moments of real community, communion with God, self and surroundings. More times when inchoate questing stumbles across a bright understanding even though no words exist to describe it. I resonate with George Steiner’s conclusion that “What lies beyond [the human ability to articulate] is eloquent of God.”

That then is my faith. God gives my ever-questing spirit some calm, a sense of direction that offers meaning, and adds the perspective of eternity. In the end it’s all a mystery.

Behind the rationalizations of all religions lies a great unknowing. This spiritual journey is strangely akin to sailors of old charting their course through the deeps, not at all certain of what lies ahead or below, but exploring headstrong into the buffeting waves. They were brave (or foolish, or forced).

What next?

The core dilemma remains: How will I be judged in the crucible of history? Will my blithe ignorance be my downfall, or will my efforts on behalf of any ultimate good be sufficient for my day? How is it possible to know whether my inner being is compassionate or self-centred? Am I building Babel, or spreading Pentecost?

I hope I am oriented in a goodly direction. I am walking by the lights I have, eager to find the moral fibre to do my bit to anchor kindness more securely in human experience.

I’d love to see a culture of forgiveness thrive, for that’s the only way to erase the cycles of enmity that plague our bickering world. Yet forgiveness is the hardest thing for any of us to do; we’re sadly loathe to let go of an entitlement in order to embrace the possibility of better relationship, be it with neighbour, country or clan. It’s an awful lot of work. It rubs against the grain. It surfaces strains of resentment running deep in our psyches. It pricks our pride. What we most need is at once so available, yet ever elusive and farfetched as well.

These thoughts could well drive me to despair. I trust they won’t. I do mourn the potential fallout of my callous or unknowing actions, and I yearn for the harsh habits of humanity to be tamed by kinder spirits. Now I wonder where any leniency might be found. What mercy is there for those whose tales entwine with tragedy? For the child soldier, what tenderness? What peace for murderers? What hope extends to the rapacious? Can grace be stretched to embrace the brutal that is bred in all, both killer and contemplative? God may know, but I sure don’t.

And so I limp along, guided by visions of an ultimate good Spirit to hear and to heed. I often see the loving resilience of grievously wounded people who have learned to live without bitterness, and whose compassion for others is the richer for their suffering. May their tribe increase. Still, the seeds of sin and saintliness lie deep within the heart of everyone. Spare me, I pray, the executioner.

– – –

Doug Koop is Spiritual Health Practitioner at HSC Winnipeg, a large downtown hospital and trauma care centre. Previously he worked as a religion journalist for 25 years. He continues to write occasional freelance articles.