By JoAnne Wadsworth, Communications Consultant, G20 Interfaith Forum

– – –

On Tuesday, June 7, the Second Interreligious Forum of the Americas (FIDELA) officially convened in Los Angeles, California in conjunction with the 9th Summit of the Americas. The FIDELA forum brought together hundreds of religious actors, civil society leaders, and policymakers for two days of discussion surrounding important issues faced by the people of North and South America. The event was co-organized by the G20 Interfaith Forum (IF20); the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace & World Affairs at Georgetown University; The International Center for Law and Religion Studies (ICLRS); Religions for Peace; and the Interreligious Council of Southern California (ICSoCal).

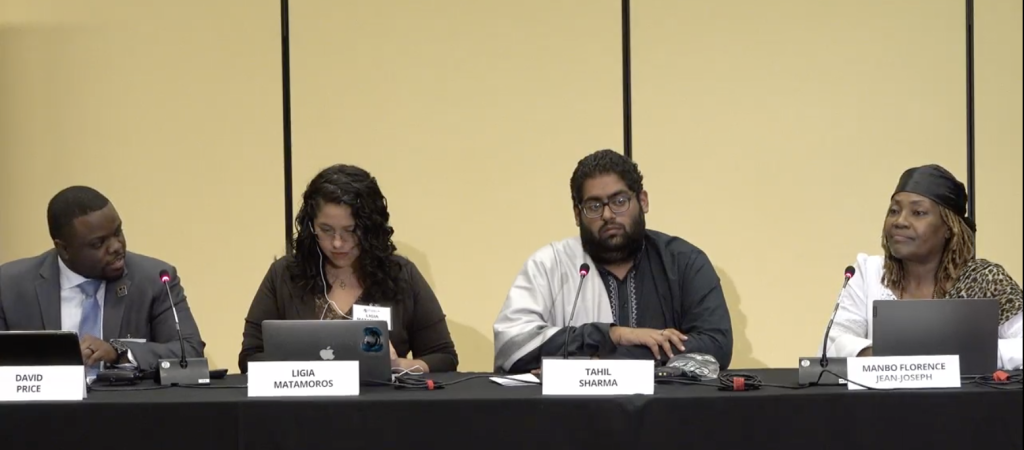

This panel, held on Wednesday, June 8 and entitled “Youth Interreligious Cooperation to Fight Racism in the Americas,” was moderated by David Price, Director of Racial Equity at the City of Los Angeles’s Civil & Human Rights and Equity Department. Panelists included Ligia Matamoros, Representative of the Latin American Catholic Youth Pastoral Ministry and Coordinator of the Religions For Peace Latin America and Caribbean Youth Network (LACYN); Tahil Sharma, Regional Coordinator for North America at the United Religions Initiative (URI) and Fellow at A Common Word Among the Youth (ACWAY); and Manbo Florence Jean-Joseph, GwetoDe for the State of New York, National Confederation of Haitian Voodooists (KNVA).

Price began the discussion by thanking the conference’s sponsors, introducing the panelists, and providing a brief framework for the topic of discussion. He said that the Americas are currently reckoning with the legacy of colonialism and the slave trade, and that Indigenous people and people of African descent are still highly affected by that legacy.

“The history of the Americas, and of religion within the Americas, is inextricably linked to the subjugation of Indigenous and Afro-descendant Peoples, but faiths also played a large role in combatting and stopping these things. How are our youth across these two continents addressing racism, and how can we help them do so?”

He then gave each speaker the floor for their comments.

Ligia Matamoros

Matamoros centered her comments on the central precept of human dignity, which is common across all faiths.

“We’ve heard many times in this forum that each person in the world has a lot of value. That’s important. However, I can’t help being a bit worried that we’re failing to receive the complete clarity regarding our actions that our faith is asking for us. I’m not trying to de-merit the inspiring actions of kindness and solidarity in our communities, but these attitudes are not yet generalized. Many still see their faiths as a reason to embrace nationalism and hate. Faith has, in the past, pushed much injustice. If necessary, we need to soften our hearts and ask forgiveness for things our faith has done in the past.”

She said she was happy that the issue was framed as a challenge for youth, as that is the space where transformative capacity truly exists.

Tahil Sharma

Sharma began his comments by recognizing that the current conversation was being held on Indigenous lands, and pointing out that though the conference was making important steps towards including women, young people, and indigenous people, there was still much work to be done. He said that true interfaith work involves solidarity with communities who have suffered in similar ways—Black communities, indigenous communities, Latinx, Asian, and more.

He then focused in on two areas where he believes interfaith work is going wrong, and what the interfaith movement needs to change in order to actually make a lasting difference:

- Interfaith cooperation in the 21st century is still unintentionally centered in White Supremacy. That’s where the leadership is still centered, which keeps the work from becoming what it needs to be and results in neutrality or even apathy instead of solidarity. These interfaith organizations are currently only ensuring religious diversity—not other types of diversity—so people who belong to minority communities don’t see themselves here.

- Interfaith work falls prey to the theology of convenience. We use religion and spirituality to talk about only what we want to talk about—and topics like racism, indigenous peoples, White Supremacy, etc. don’t get talked about because they’re too political, too inflammatory, too unrelated to the organization’s mission. Then justice and equity don’t see the light of day because we aren’t willing to get uncomfortable.

Manbo Florence Jean-Joseph

Jean-Joseph also touched on the importance of dialogue and uncomfortable conversations in her comments. She said that in her journey as a Manbo, she has learned several things—namely to have compassion for the world though the world doesn’t have compassion for her, and to focus on the present to replace guilt and fear with love.

She said that though faith communities are important influences in the fight against various evils, they’ve also had a hand in generational trauma and more. Though faith often promotes resignation, we need to use it as a motivator for action. We must collectively process this trauma together and act, identifying the pieces of major Western faiths that perpetuate oppression.

“Faith alone cannot address the history and implications of slavery and colonialism, which have not ended. We need to bring our youth to the table to fight racism. Our children are living things we don’t understand. We cannot be politically correct. We cannot shy away from being uncomfortable. We cannot see this issue as ‘not our problem.’ It’s our problem and our issue, and only when we truly identify the problem can we find points of healing and make a better world where our children can safely speak their stories.”

Q&A Session

How can interreligious youth networks come together to address racism? How can people mobilize to do this work?

Manbo Florence Jean-Joseph:

We must recognize our own biases and understand that we all see things in slightly different ways. We unconsciously favor some over others—and it’s a very deliberate exercise to learn to love all equally. As leaders, we must consciously ask for, work on, and spread that love.

Ligia Matamoros:

To actually change attitudes, we must create spaces that allow us to meet people—spaces that give people from these marginalized groups faces as individuals. And if we’re going to put this issue on the shoulders of our youth and expect them to make a difference, we also need to take a chance as faith communities and give our youth real opportunities to participate and promote change. You can’t give youth the responsibility without the power.

Tahil Sharma:

If we want to get interreligious networks of youth mobilized, we need to center their voices, period. We need to stop sidelining them, treating them as tokens, or calling them “the future.” Their leadership needs to be taken seriously now, instead of making them wait for permission to enter the gates.

What “reality checks” do we need surrounding this topic?

Manbo Florence Jean-Joseph:

What you should know and what you know are two different things, and you do what you know. Each generation has what it knows—its own story. We need to recognize that younger generations are facing an unprecedented amount of fear, and we must create safe spaces for them.

Ligia Matamoros:

We need to recognize the power of stories. We know many stories, but not all—and we need to strive to know and share ALL stories, because that’s what creates our perceptions of others. It’s necessary that communities share and disseminate the stories of those who are underprivileged and don’t have the platforms to tell their own stories.

Tahil Sharma:

If we’re going to invite folks from various communities to represent themselves, we need to let them define who they are instead of putting them in the box of their community definition. No person exists in a monolith with their faith traditions and communities. They have shared values and connections, but each person’s experience is different.

Youth are statistically losing trust in institutions and leaving organizations, including religious ones. As interfaith institutions, how can we better understand this phenomenon and better engage these youth?

David Price:

Institutions want to be safe and protect themselves, and therefore don’t allow much room for vulnerability—making them come off as stiff and stale and unwilling to push the margins. Young people are looking for safe spaces where they can fully show up as themselves. Institutions have to take the time to understand what vulnerability young people are looking for, then be courageous enough to step into that.

Ligia Matamoros:

There’s no doubt that our religious institutions have done things they shouldn’t have done, and young people want coherence from faith institutions. We would like to see changes. We want our religious communities to be open and listen to what we’re asking for. We need connection that goes beyond photo ops.

Tahil Sharma:

When you live in a reality where religion is a two-sided coin that can be both disastrous and deeply beneficial, it’s manipulative to show just one side. Let people learn the truth: This is a religion, which has baggage, but also has a lot of really good things. It’s not actually that hard for young people to deal with that truth.

How can we strengthen anti-racism work as interfaith communities?

Manbo Florence Jean-Joseph:

Living beings are to be respected. That is of utmost importance. It isn’t for us to judge. This is an issue of letting go of that control and replacing it with love, and using money as a tool to help instead of letting it be the master of our heart.

Tahil Sharma:

When a faith community has more money than some countries, you have to question what they’re using it for. If you aren’t using it to benefit the marginalized and oppressed, you’re effectually creating the golden calf. And above that, if you’re just giving but not changing the systems that created these cycles of poverty, you aren’t being genuinely charitable.

Ligia Matamoros:

Since we’ve been silent in the past in regard to these hard topics, we need to be extra present now. Indigenous and Afro-Descendant people have limited access to opportunity. They’ve been tremendously resilient. We as faith communities need to start admitting and apologizing for our wrong actions, building bridges of reconciliation, and collaborating to solve these systemic issues.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Price thanked each of the panelists, saying that there was richness and value in the personal truths that they’d shared. He also once again thanked all sponsors and audience members, and ended the panel with the hope that people would be healed and work would be pushed forward to continue to do good.

– – –

JoAnne Wadsworth is a Communications Consultant for the G20 Interfaith Association and acting editor of the “Viewpoints” blog.