By Dr. Helen Rosenbaum, Deep Sea Mining Campaign

– – –

Introduction

The largest open cut mine in the history of the world is poised to start in the backyard of Pacific Island states. However, the very peoples whose livelihoods, economies, and cultures would bear the brunt of the impact are yet to have their voices heard in formal decision-making fora.

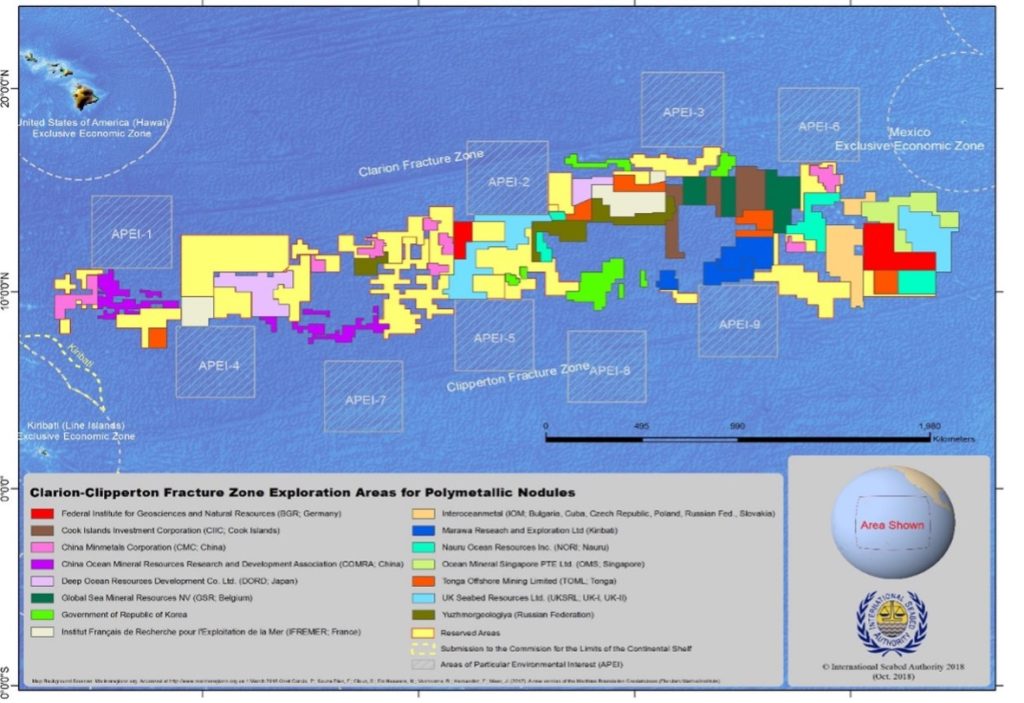

The Pacific Ocean is the scene of a new wild west. Companies and their investors, hungry for profits, are driving a speculative rush for seabed minerals. The Clarion Clipperton Zone of the Pacific Ocean, stretching over 5000km between Kiribati / Hawaii and Mexico has an abundance of polymetallic nodules. Its seafloor is a patchwork of exploration licenses issued to corporate and corporate-government entities by the International Seabed Authority.

Pacific Spirituality vs Corporate Greed

For hundreds of generations, Pacific peoples, living on thousands of islands, have sailed, fished, and traded across the immense Pacific Ocean. In their traditions, the sea is not understood as an empty space between land masses but as intrinsic to society, spirituality, and identity. Pacific people are connected to their vast ocean, and through it, to each other.

Pacific relationships with the ocean should be the starting point for discussions about deep sea mining (DSM). However, the Pacific DSM industry, driven by a handful of companies with narrow commercial agendas, has brokered deals largely ‘behind closed doors’ with Pacific Island states. Most Pacific Islanders, and in fact people worldwide, are not aware of the magnitude of the ambitions of this emerging industry and how close it is to destroying the fragile ecosystems of the deep sea.

In the Pacific, companies plan to send monstrous mining machines to the sea floor within the next few years. The most aggressive of these, The Metals Company (TMC), has tried to force the hand of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) to rush regulations to allow commercial mining via a legal loophole triggered by its Pacific Island sponsor, Nauru. This could allow TMC’s subsidiary Nauru Oceans Resources Inc (NORI) to submit an application to mine this July whether or not regulations are in place.

If they succeed, the DSM floodgates will be opened.

The video Blue Peril presents a scientifically robust visualisation of how far-reaching the impacts of deep sea mining (DSM) are likely to be for marine ecosystems and Pacific Island communities and their economies. It incorporates the best publicly available data into internationally accredited oceanographic and spatial imagery programs to predict the spread of plumes that will be generated and the scale of destruction of deep seafloor ecosystems.

Blue Peril predicts that TMC would destroy an area of seabed similar to the land area of the whole of Hawaii in 30 years – the license period it may be granted. This modelling was conducted for TMC’s Nauru (NORI D) licence area, though it has several others.

The International Seabed Authority – regulating in whose interests?

The ISA is an autonomous body set up under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, charged with managing the resources of the deep seabed in areas beyond national jurisdiction. Its mandate includes protecting the interests of humankind as a whole and the ecosystems of the deep sea.

Significant concerns have been raised about the lack of transparency and independent scrutiny in ISA processes, and also about serious conflicts of interest due to its cosy relationship with the mining companies it is mandated to regulate.

The ISA Assembly represents the full membership of 167 countries plus the EU. It allows civil society to observe and to make interventions, but to take no role in decision-making.

However, it is this closed, 36-member ISA Council where critical decisions will be debated about–whether to close the two-year loophole, and how to assess any applications made under it.

The ISA Secretary General has for too long run this body out of the glare of public scrutiny, but member countries are now starting to realise that they must flex their muscles to avoid irreversible damage to our deep ocean, its unique ecosystems and its role in carbon sequestration. 21 ISA member countries now call for a ban, a moratorium until scientific gaps are filled, or for no mining without robust regulation. What is your national Government’s position?

Right now and until 28 July, Governments from around the world are meeting at the International Seabed Authority in Kingston, Jamaica, to develop regulations that, if agreed upon, could see the biggest mining operation in history begin in our ocean.

This is a critical opportunity for us all to raise our voices in support of a moratorium and urge our own governments to do likewise. You can follow the negotiations at the International Seabed Authority via the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition’s deep sea mining negotiations tracker and can send messages to or tweet directly your relevant ministers, calling on them to support a moratorium at the ISA.

———————————————————————————————–

What’s at stake?

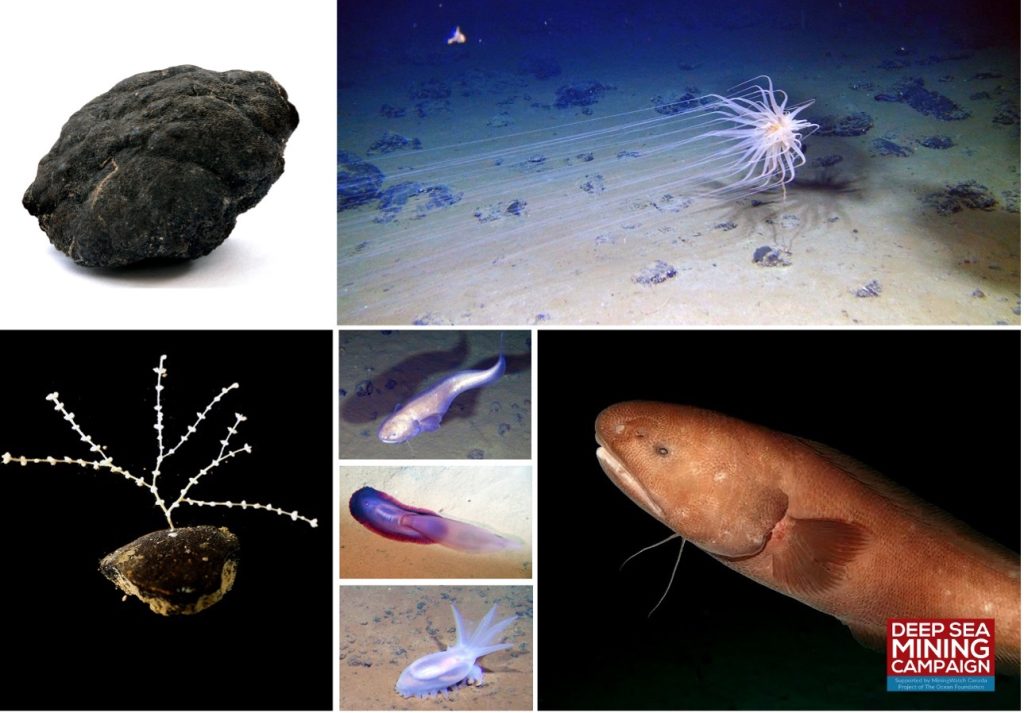

Nodules provide hard surfaces for attachment, animals forage around them and lay their eggs on them. Because Nodules take millions of years to form, their removal would remove this habitat and the species that rely on them for millions of years. Very little is also known about the connection between the ecology of the upper layers of the ocean with the deep sea. However, science is slowly catching up to what Pacific Islanders have already known: we are all in one interconnected realm. We are gradually understanding that the deep sea is likely to play an important role in carbon cycling (climate change) and is connected to upper layers by deep diving animals such as Cuvier’s Beaked Whales and Sperm Whales. The interconnectedness of the ocean – horizontally and vertically – means that what happens in the deep won’t stay in the deep.

Report after report lays bare the facts regarding the declining health of the world’s oceans and the unparalleled rate of extinction of the world’s biodiversity, warning of alarming implications for human health, prosperity and long-term survival.

The stakes are high — irreversible damage to marine ecosystems that support the many (via national economies, food security, livelihoods, spiritual and cultural connections and potential biomedical) versus the narrow commercial interests of primarily a handful of investors.

– – –

Dr. Helen Rosenbaum is co-founder of the Deep Sea Mining Campaign. Helen holds a doctorate in Medical Science, has worked as a marine toxicologist and in the development of coastal management policy. Over the past 12 years the DSM Campaign has worked in solidarity with civil society organisations, scientists and citizens around the world who are concerned about the likely impacts of deep sea mining. The DSM Campaign is a member of the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition.