By Ja:no’s–Janine Bowen, Director of the Seneca Language Department, Allegany Territory, Seneca Nation

– – –

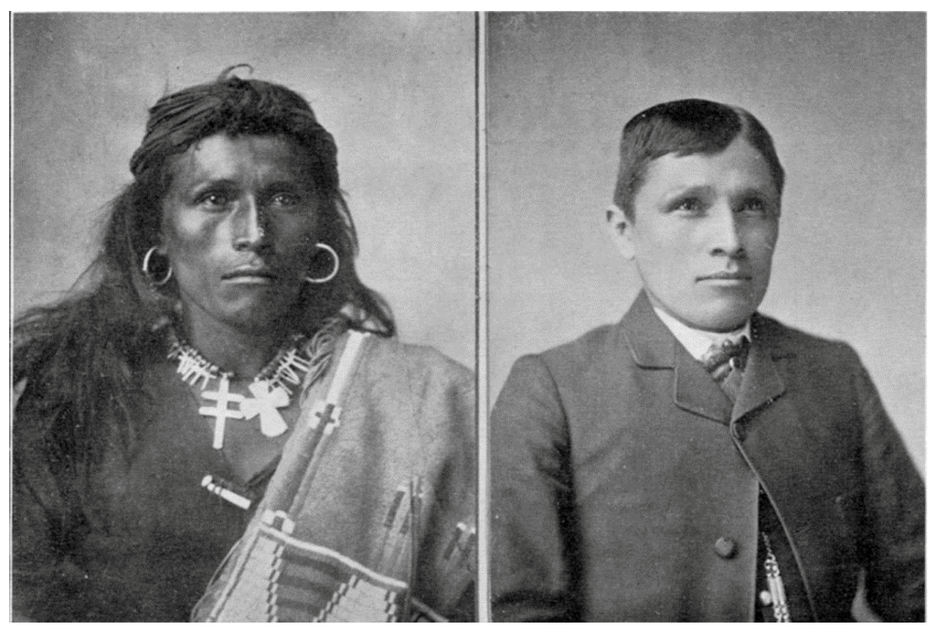

“Kill the Indian, and save the man.”

That was the motto of the Indian boarding schools in the United States and Canada between 1831 and 1996, when the last Canadian residential school closed.[1]

Survivors and Their Struggle to Heal

Despite consistent efforts by government and religious organizations to annihilate Native nations by eradicating their cultures, many are still intact. While some languages have been lost, many are being revitalized. Ceremonies continue; songs are sung; and many Indigenous peoples live on.

However, the struggle to heal from years of forced assimilation and abuse continues to plague the families of many survivors. Survivors describe traumas such as forced removal from their communities, loss of cultural practices, and loss of language—as well as psychological, emotional, verbal, physical, and sexual abuse.

Symptoms of Intergenerational Trauma

Intergenerational trauma among the Indigenous communities of the U.S. and Canada continues to cause a distrust of school systems, psychological distress, substance abuse, and high rates of suicide.

The impact of Indian boarding schools has been passed on across the generations due to a lack of acknowledgement, awareness, and healing. In many cases, these negative impacts continue to cause the families of survivors to display symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder, such as perpetuated cycles of abuse, poor parenting skills, chronic depression, rage, unresolved grief, spiritual confusion, and early death.

Despite all this, for a long time discussions of the topic remained hidden, like the children buried in unmarked residential school graves. Nevertheless, several Native communities have begun the slow and painful journey of healing from the abuses carried out at Indian boarding schools.

Acknowledgement: The First Step to Healing

While Indigenous communities in the U.S. and Canada strive to heal from the damaging effects of residential schools, supporters and allies must work to educate themselves and the Canadian / American public about the horrific history and its harmful impact on both American Indian individuals and their communities.

Education leads to acknowledgement, an essential first step to healing the trauma. However, there are citizens of the U.S. and Canada who refuse to believe that their governments and religious organizations would carry out cultural genocide, despite copious documentation. Such blatant denial assists in perpetuating the institutional racism that lingers in educational systems throughout the U.S. and Canada. Even if others acknowledge the abuse suffered by Native children in boarding schools, they often minimize the intergenerational trauma and wonder why the Indians cannot “get over it.”

As the G20 Interfaith Forum continues to advocate for educational programs that promote equity, inclusion, and well-being, let us ensure that countries safeguard the healing of residential school survivors and their communities through education.

[1]While many Indian boarding schools continue to operate in the United States, they are no longer mandated to, “Kill the Indian, and save the man”.

– – –

Ja:no’s—Janine Bowen is a member of the Beaver clan of the Seneca Nation and a Faith Keeper at the Cold Spring Longhouse. She has centered her career on Seneca language revitalization efforts. In 2002, she began teaching Seneca language and culture to elementary and junior high school students on the Allegany Territory of the Seneca Nation. In 2007, at the request of the Allegany Education Director, Ja:no’s became a Seneca language Instructor for Buffalo State College. In 2015, the Seneca Nation Chief of Staff encouraged her to take on the role of Allegany Territory Language Director at the Seneca Nation. Ja:no’s received an Ed.M. from the Harvard University Graduate School of Education, as well as an M.P.P. from the Harvard University Kennedy School of Government. In 2020, Ja:no’s started her path back to the field of education when she began coursework for an MSED in Educational Leadership. It is her goal to merge her talents to support indigenous students in their journey to become successful individuals capable of overcoming the unique challenges Native peoples face as they learn to walk in two worlds.