By Katherine Marshall, World Faiths Development Dialogue (WFDD), Berkley Center

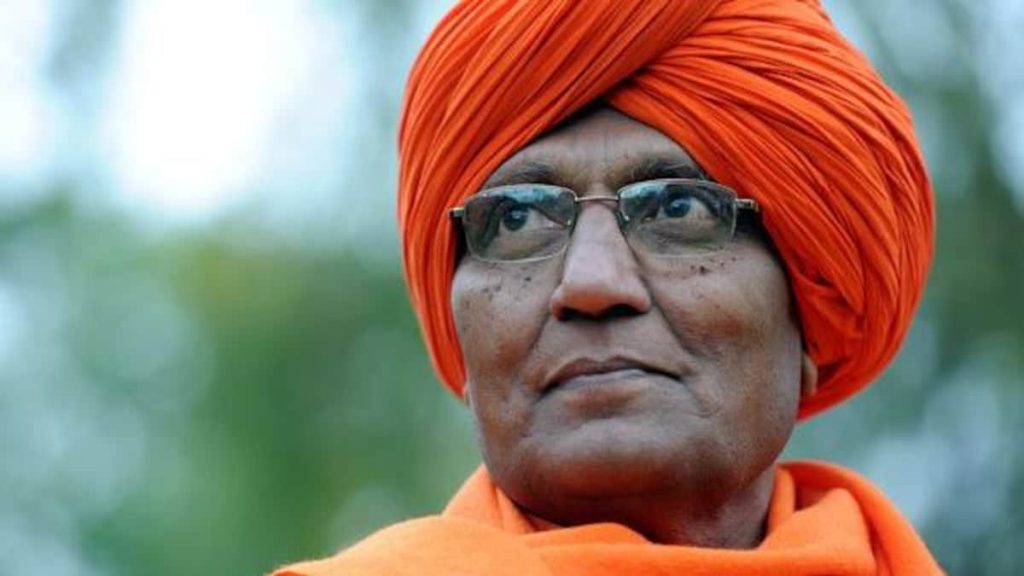

What words and what examples come to mind when asked to highlight Swami Agnivesh’s example for the upcoming generation? For those who must take this extraordinary moment when the COVID-19 emergency has thrown so many accepted norms and normal patterns into questions, what can they learn from this remarkable, truly unique force of nature?

A Legacy of Speaking Truth to Power

For me, he exemplifies a quality we devoutly wish for and need to see in spiritual and religious leaders: the courage to speak truth to power. Often uncomfortable truths. Spoken with clarity, no beating around the bush or mincing words. That truth-telling needs a kind of “no holds barred” courage and a commitment to truth. And to whoever is in power, whether they want to hear it or not, this is an example that is sorely needed today, when there is far too little truth and far too little courage. This quality of Swami Agnivesh and the example he set go alongside a constant compass that is focused on those who suffer and who are vulnerable. He spoke and acted from a deeply considered commitment to justice and fairness.

I met Swami Agnivesh not long after being tapped by World Bank James Wolfensohn (in 2000) to translate an idea and ideal of dialogue between religious and secular leaders committed to development into reality. That challenge initially focused on two forms: first, meetings that brought together people from the two groups, and second, looking beyond warm statements that included an undue dose of platitudes to understand better the reasons for discord and, still more, hostility and indifference. I have thus had the privilege of meeting Swami Agnivesh often, in very different settings, in different corners of the world. We have also corresponded and spoken on other occasions. We shared a panel discussion on the role of faith in the Asia Pacific region in early July this year, as part of the United Nations High Level Political Forum.

Two interviews that I did with him and wrote up explored how he came to his sui generis role: spiritual leader ready to contest and fight, skeptic about organized religious bodies, willingness listener, dreamer of a better world. These interviews are part of a collection on Georgetown University’s Berkley Center website. They highlight an unusual journey and his robust commitment to truth and justice.

An avalanche of memories of the striking figure who took on topics ranging from hunger to HIV/AIDS to slavery should make a book. I treasure the memories and the orange headpiece that he put on my head twice during meetings, a testimony to a special friendship.

Three Examples

Three moments I was part of illustrate Swami Agnivesh’s witness and his lived example.

During a visit to India, Swamiji invited me to visit a site where bonded laborers – children for the most part – had been freed. They had been enslaved as brickmakers. The visit involved an overnight train trip and a public gathering marking the events. At each point as people approached and wanted to bow to the Swami he resisted: people are equal and traditional obeisance to religious figures is inappropriate, he said. He inspired a crowd gathered to celebrate but also spoke to individuals about their fears and hopes for the future.

At a meeting in Indonesia in 2003 to reflect on a draft Universal Declaration of Human Responsibilities, a notable group was assembled, many former heads of state and learned figures. Balancing rights and responsibilities was the topic of the day. It was the eve of the invasion of Iraq and many expressed their doubts about the wisdom of what seemed the inevitable impending events. Swami Agnivesh suggested that the group move, one and all, to Iraq to serve as a human shield. I wish I had more than a mental image of the faces of his audience. Needless to say there was no mass move towards Iraq but the challenges was clear: one should be willing to act on one’s words and beliefs.

In Rome, Pope Francis visited the World Food Programme headquarters there to support global efforts to end hunger, which is the thrust of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 2: Zero Hunger. In an interfaith discussion the day before, Swami Agnivesh spoke forcefully and with no political correctness about the underlying injustices that cause hunger. He also called for action beyond words. His few words to the Pope conveyed the same sense of urgency, care, and commitment to and belief in the common purpose that was the essence of the event.

Ideals to Action

The palette of Swami Agnivesh’s life work is filled with intersecting colors and textures, reflecting vividly the deeply interconnected aspects of both justice and cruel wrongs. His work to fight modern slavery translated to commitments to rights of children, women, class, and castes. His commitment to education reflected a deep faith in the potential of humanity, given the chance. His interest in HIV/AIDS left aside causes of disunity and focused on compassion and action. Despite some well-founded doubts about the benefits of interreligious dialogue events where many disagreements and tensions remain masked, Swami Agnivesh never hesitated to engage with a spirit of moving the dialogue forward, attending several G20 Interfaith Forum events, among others.

The complex threads of religious roles in conflict, in India and elsewhere, drew Swami Agnivesh into active roles in conflict mediation and into courageous stances calling for truth and justice. His courage and willingness to take on powerful interests are noteworthy, even notorious. When the voice of the voiceless and their welfare is at stake, it is the time to act.

That’s central to his legacy and example: Not only must a true leader speak truth to power. They must work constantly to carry ideals into action.

Professor Katherine Marshall is a senior fellow at the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs at Georgetown University. She serves as the executive director of the World Faiths Development Dialogue and worked at the World Bank from 1971 to 2006, tackling development issues in the world’s poorest countries.