By JoAnne Wadsworth, Communications Consultant, G20 Interfaith Forum

– – –

On Monday, June 13th, the G20 Interfaith Forum held its fifth webinar of 2022, organized by its Anti-Racism Initiative and co-sponsored by the International Academy for Multicultural Cooperation. Panelists included Abbas Barzegar, Director of the Horizon Forum and Team Member of the Council on Foreign Relations; Amir Hussain, Chair and Professor of Theological Studies at Loyola Marymount University; and Reyhana Patel, Director of Communications and Government Relations at Islamic Relief Canada. Christina Tobias-Nahi, Director of Public Affairs at Islamic Relief USA, moderated the discussion.

Christina Tobias-Nahi, who acted as moderator for the event, began the webinar by welcoming all panelists and viewers and putting this webinar, focused on Islamophobia, into the context of the wider series of webinars being held by the IF20 Anti-Racism Initiative. She then explained that the main focus of the webinar would be on Islamophobia in Canada and the USA, for the sake of time zone alignment and simplicity—and because the Muslim population of the world is so widely diverse. After giving a nod to an activity taking place on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C. that same day, where Muslim communities were lobbying for a designated envoy to combat Islamophobia, Tobias-Nahi introduced the speakers and gave them the floor.

Reyhana Patel

Patel focused her comments on Islamophobia happening in Canada on the personal level, citing a recent report compiled by Islamic Relief Canada where stories were collected from Muslim people across Canada about their experiences with anti-Muslim hate. You can read the report in full here.

“When we talk about Islamophobia, we read and hear about the political implications, but the consequences of hate for ordinary people are often overlooked. Some of these stories in the report are so powerful.”

Patel referenced several stories from the report, including a teacher in Quebec City’s experience fighting Quebec’s discriminatory “no religious symbolism in the workplace” law to keep her headscarf, boys at school ripping off a girl’s hijab, a woman experiencing jeering and workplace discrimination after deciding to begin wearing a headscarf, a man paralyzed from the waist down in a mosque shooting, and more. She said Muslim women are most often victims of these acts of hate, and that victims typically dismiss their experiences and fail to submit a report.

Interestingly, Patel also said she’s observed how these experiences with hate also increase determination and resiliency in Muslim communities, with victims feeling an increased commitment to their faith and to changing Canadian policies.

Though Canada has a reputation as being very inclusive, multicultural, and tolerant, Patel said the country actually leads the world in publishing far-right supremacist online content. In the past ten years, more Muslims have also been targeted in violent hate crimes in Canada than in any other country—with large scale mosque shootings, a family getting run down by a car, and a man getting stabbed as he left his mosque as just a few examples.

“Islamophobia is systemic, it’s gendered, and it’s normalized within every level of society. This normalization is what leads to these attacks. People don’t wake up one day and decide they’re going to storm into a mosque and shoot a bunch of people. It’s a process.”

Amir Hussain

Hussain chose to focus his remarks on the diversity within the American Muslim community and their contributions to various Civil Rights and Anti-Hate movements throughout American History.

“We don’t often think about the diversity within the American Muslim community. 25 to 35 percent are African American—many of whom have been both Muslim and American for centuries. Islam goes back in America almost 500 years, back to the transatlantic slave trade. A third of American Muslims are Southeast Asian. A third are Middle Eastern. And in LA where I live, there’s a strong Latino Muslim Association.”

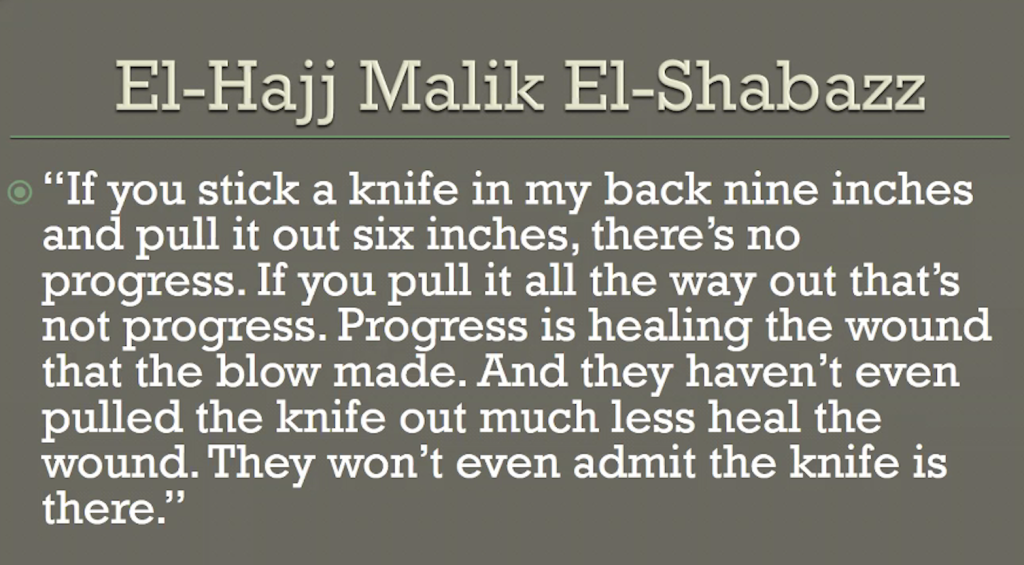

He referenced the integral roles that many American Muslims played in social civil rights movements in the 1960’s, including Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X. Hussain also referenced Keith Ellison, the first Muslim elected to congress (2007), who acted as the Attorney General covering the prosecution of George Floyd’s murderer in Minnesota last year.

“We sometimes forget that history of diversity within this community and its potential connection to racism as well. We don’t think about the ways in which Muslims were involved in civil rights programs. American Muslims are often on the forefront of anti-discrimination work.”

Abbas Barzegar

Barzegar centered his comments on institutional violence and hate—and what that looks like.

“Islamophobia and anti-Muslim hate are endemic in our society. They’re not simply opinions people have about Muslims or Islam. They manifest in actual policy and institutional violence, which affect millions of people’s lives. It’s one thing to talk about the pervasiveness of these attitudes, but it’s harder to get our heads around how they manifest institutionally.”

As examples of these attitudes-turned-laws, he referenced President Trump’s proposed “ban” on Muslim Immigration, which was stopped in that form but made it quite far down the policy initiative pathway. He also referenced the laws against religious symbols in Canada and France, and the tight restrictions around the construction and architectural design of mosques in many European nations.

In answer to how these initiatives got so far as to become law, Barzegar presented an example unique to the US context: that of Donor-Advised Funds (DAFs). These funds behave like charitable checking accounts, where foundations hold donors’ money like a bank would until the donor decides where they’d like to distribute it. When donations are eventually made, they’re made under the name of the DAF instead of the donor, so it provides an effective method for people to fund hate groups (cleared as nonprofits) without their name being attached. Barzegar’s organization, the Horizon Forum, spends much of its time finding these hate groups and bringing them into the light.

“We’ve given up on the idea that we can completely stop this problem legally. We have to coach people on a risk management and values alignment perspective to implement due diligence and anti-hate policies as leaders in their organizations and society at large. Let’s stop counting on government to do the job for us.”

Q&A Session

What do you do to change overarching narratives about the Muslim community?

Reyhana Patel: “I didn’t expect a lot of my work to be combatting hate—honestly I expected to be spending most of my time promoting the good things that Islamic Relief and the Muslim community at large does. But 50 to 60 percent of my work is dealing with hate instead of spreading goodness, doing research, and working on community engagement.”

Christina Tobias-Nahi: “Islamic Relief USA does a lot of disaster recovery work, often in places where people have never met a Muslim before. So when they see our vests, that changes attitudes. So does our work with refugees.”

How do Islamophobia and hate factor into struggles Muslim refugees are facing?

Abbas Barzegar: “There are 100M refugees around the world, with at least 60 percent of them coming from Muslim communities. Nationalism is rising, and communities are becoming more insular and exclusive. Hate activity comes up when people talk about immigrants with these hyperbolic sentiments—for example fearing that these people are criminal gang members, that they’re terrorists, that they’ll bring diseases we’ve never experienced or extract resources and take over our communities. Tens of millions of dollars are being funneled into supporting these narratives via hate groups with 501-C3 status. There are whole books and treatises written about the Great Replacement Theory, etc.”

Did Islamophobia begin with 9/11? How does violent extremism factor into these narratives?

Abbas Barzegar: “Violent extremism across the globe now includes multiple ideologies, including white supremacist groups and more, but a large part of the global move to combat violent extremism is grounded in combatting violent extremist groups claiming the Muslim faith. We need to recognize what those organizations are, what their backgrounds are, and more. If you understand the demographics and histories of these groups, there’s no reason to assume that a refugee suffering from mental health issues is a security risk. People don’t have to be on guard against every Muslim. We need to keep these movements separated from ideology and fear—but when we have a broad policy governing this issue, it’s difficult to control the mission creep that happens, where security systems are getting their fingers into social service work and more.”

Christina Tobias-Nahi: “People who call into mental health support lines with Muslim-sounding names are immediately flagged on national security databases. We don’t need to be targeting these communities—they need more resources, support, and help than ever.”

Amir Hussain: “Islamophobia didn’t start with 9/11. There were big issues with it in the 1970s, in the gas lineups in LA, and more—all the way back to eras like the Crusades. I’m so thankful for these organizations that are working to address this.”

Reyhana Patel: “We need more education, more conversation. Bringing people together and increasing understanding is essential.”

Conclusion

After each speaker offered brief concluding remarks, Tobias-Nahi thanked both audience members and participants and highlighted the importance of these conversations being held on the fringe of the G20—especially with Indonesia (a Muslim majority country) as the G20 host this year and India (a Muslim minority country) as the host next year.

– – –

JoAnne Wadsworth is a Communications Consultant for the G20 Interfaith Association and acting editor of the “Viewpoints” blog.