By JoAnne Wadsworth, Communications Consultant, G20 Interfaith Forum

– – –

On February 23, 2023, the G20 Interfaith Forum’s Anti-Racism Initiative, in cooperation with the Tanenbaum Center for Interreligious Understanding, the International Academy of Multicultural Cooperation, and the United Religions Initiative (URI), held a webinar entitled “Religicide: Examining Religious, Ethnic, and Racial Violence.”

Speakers included Dr. Georgette F. Bennett, Founder of the Tanenbaum Center for Interreligious Understanding and the Multifaith Alliance for Syrian Refugees, and Author of “Religicide: Confronting the Roots of Anti-Religious Violence”; Jerry White, Executive Director of the United Religions Initiative and Author of “Religicide: Confronting the Roots of Anti-Religious Violence”; Sister Makrina Finlay, Benedictine Nun at St. Scholastika Abbey (Germany), Historian, theologian, Yazidi researcher, and humanitarian; and Karen Volker, Director of Partnership and Violence Prevention at the United Religions Initiative. Audrey E. Kitagawa, Founder/President of the International Academy for Multicultural Cooperation and Chair of the G20 Interfaith Forum Anti-Racism Initiative, moderated the discussion.

Audrey Kitagawa began the discussion by introducing the work of the IF20 Anti-Racism Initiative and the concept of “Religicide,” which is thoroughly explained in a book recently released by two of the panelists. In that book, Religicide is defined as follows:

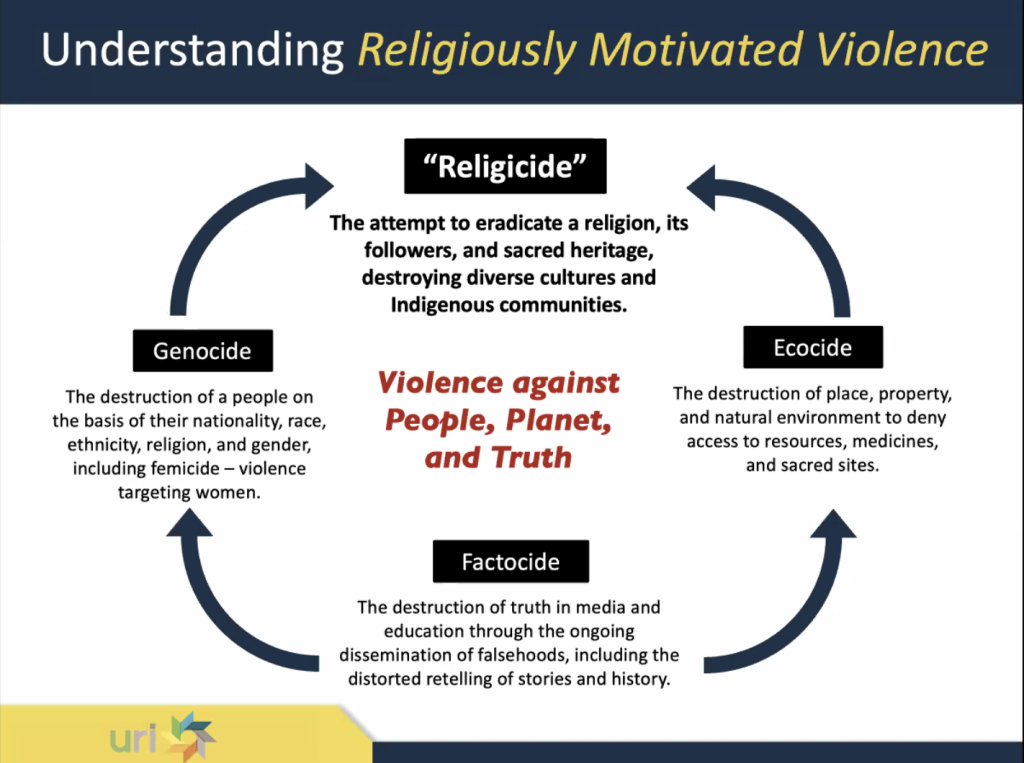

Religicide: A systematic attempt to eradicate a religion, its followers, and its sacred heritage, destroying diverse cultures and Indigenous communities. These diverse attacks include ecocide, factocide, and genocide.

Kitagawa said that current international legal instruments have gaps that do not cover Religicide, then invited each of the speakers to offer their prepared comments.

Dr. Georgette F. Bennett

Bennett began her comments by explaining her personal connection to the study of religion and religious violence. Her grandparents died in the Auschwitz complex in Poland during the Holocaust, and she and her family arrived in the US as stateless refugees. 71 years later, she is still studying issues connected to that tragedy.

She said though the Holocaust led to the codification of Crimes Against Humanity and Genocide, and since then Ethnic Cleansing and War Cleansing have also been codified, none of these terms fully encompass Religicide.

“Religicide is the attempt to wipe out an entire religion and its cultural heritage. It includes ecocide, factocide, and often suicide. And it slips between the cracks of our current human rights infrastructure, going unrecognized, unaddressed, and unabated.”

Bennett said Religicide always starts with hate speech—words that empty others of their humanity and make them caricatures of contempt. Most genocides begin with leaders spewing hate speech, and some of the roots of hate speech can even be found within religions themselves (group narcissism, the “children of light” vs the “impure,” etc.). However, hate speech is precisely where interventions must happen to stop Religicide from happening.

She added that a major reason that Religicide slips through the cracks is that international legal language surrounding religious intolerance or freedom of religion or belief (FoRB) is limited to mere declarations, not laws, and that criminal punishment for religious discrimination is left up to local countries to pursue. Nothing is enforced on a global scale.

Jerry White

White focused his comments on the causes and contributing factors of Religicide, and how to address each of those in society. He showed Religicide as a Venn diagram, where Factocide, Genocide, and Ecocide meet.

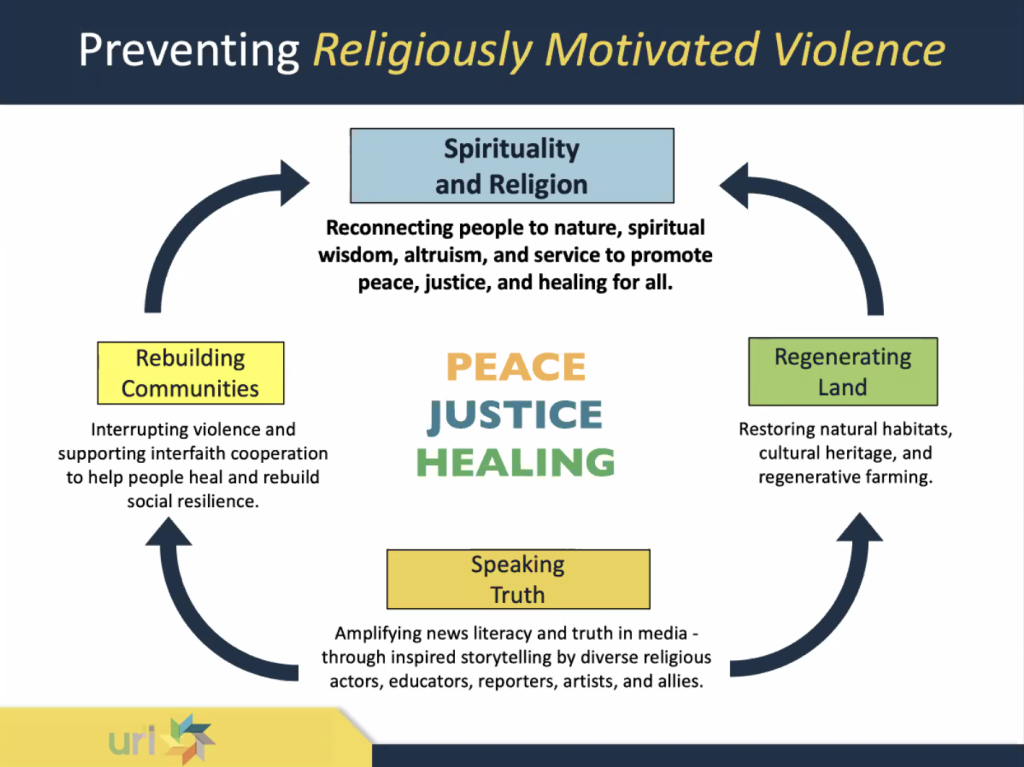

As violence, lies, and environmental destruction contribute to Religicide, White said that preventing Religicide is a matter of focusing on the opposites in our communities.

He said that religion is not the source of most of the world’s conflicts—those conflicts already exist, centered around power, territory, and glory, and then become “religified” because religion is a very effective way to sustain a group. With 84% of the world identifying as religious, perpetrators of violence are just a very small group of instigators, and the rest are silent believers who love peace, justice, and healing.

White asserted that religion and spirituality are key to getting out of the problem of violence, citing a study that listed things that were key to resilient, thriving communities: optimism, altruism, a moral compass, faith & spirituality, humor, role models, social support, facing fears, having a mission, and mentorship/training. Many of these things are intrinsic to religion and spirituality.

Sister Makrina Finlay

Finlay centered her comments on her experiences with the Yazidi people, who have been victims of Religicide. She first became involved in the Yazidi community of refugees in Germany, and has since immersed herself in learning about the community’s experiences since the genocide in 2014 and long before that.

The Ezidi people are an Indigenous religious and ethnic minority from Iraq, Syria, and Turkey, currently with about 800K-1M members post-genocide. Their complex and all-encompassing socio-religious practices and culture has been misrepresented and demonized over hundreds and hundreds of years, justifying violence and destruction of land and culture. According to Yazidi tradition, they have historically experienced 72 genocides.

Finlay explained that understanding Religicide is helpful in the Yazidi context because it helps the people understand what they’ve experienced, and it shows that true recovery requires a holistic approach. As the attack on Yazidis wasn’t just genocide—it included culture, context, facts, places, farming ecosystems, etc.—the microcosmic and macrocosmic elements of the destruction must be recognized in reconstruction.

Karen Volker

Volker focused her comments on her study of interrupting and stopping violence in communities. She said it is indeed possible to interrupt and stop religiously-motivated violence, and advocated for a new perspective on violence as a disease of sorts:

“We need to look at violence through a health lens. It isn’t a bad person. It’s a behavior that spreads in a contagious manner and can be prevented.”

She said prevention or interruption happen in three steps:

- Detect violence and interrupt it before it happens (this must be done by those who are close to the people doing the violence or giving the orders).

- Change the behavior or the highest risk (focusing on areas where there are high levels of religiously-motivated violence instead of trying to cover all areas).

- Change the norms (Violence happens in a context where it is “normal” or accepted, but faith leaders and actors can change these norms).

Volker further emphasized that violence prevention/interruption approaches must be holistic, with top down involvement from governments, middle out involvement from all of us changing norms, and bottom up involvement where it is stopped at the local places it happens.

Question and Answer Session:

Who is being trained to interrupt violence, and how?

Dr. Georgette F. Bennett:

The Tanenbaum Center’s “Peacemakers in Action” program trains people in conflict resolution and peacemaking skills. We also train diplomats to work with religious actors. Cambridge University Press has published two books full of our case studies in peacemaking, available on Amazon and elsewhere.

What can we as individuals do to make the most difference?

Sister Makrina Finlay:

Start close to home. Get to know the marginalized people in your communities, and then ask them what their needs, dreams, hopes, and challenges are.

Karen Volker:

Anyone and everyone can push back against hate speech. Call it out. Name it when you see it. You can demand from your own faith leaders that they speak out against religiously motivated violence. To paraphrase Ghandi, we need to gently shake the shoulders of the world.

Can you share more about the gaps in international law that Religicide is slipping through?

Georgette Bennett:

There are extensive gaps in international humanitarian, criminal, and refugee law. The various resolutions that address pieces of it don’t have the force of law behind them, and even the accepted laws that do aren’t currently very enforceable. The concept of national sovereignty is currently central to our system and has left it tied up in knots with a lot of gaps. What do you do when states are being horrible to their own people, but it isn’t crossing borders? What about non-state entities like ISIS?

Concluding Remarks

As the session ended, Kitagawa invited each of the panelists to offer closing remarks.

Jerry White:

In the book, we suggest the concept of a global covenant of religions. People of good faith are cross-border entities. The system divides and conquers. All of these religions and people of good faith coming together in a global covenant to pursue justice, peace, and healing would create serious waves. But we need to overcome the challenge of being so siloed in our work—with genocide being a different office than ecocide which is a different office than hate speech, and each religion advocating separately.

Georgette Bennett:

It begins with us as individuals. Individuals truly can make a difference. Here is my formula for being a change agent: Find an entry point, identify a gap that isn’t being filled, find something doable with which to fill that gap, and stay tightly focused on that. It’s easy to get paralyzed into inaction when you look at the big picture, but not when you follow that formula.

Sister Makrina Finlay:

As important as it is to find your own spot, you must also recognize that your spot is part of a whole. The clearer my lens, the more I understand my role in the bigger picture. And recognizing that we’re part of a whole leaves room and respect for other perspectives. That’s where true change can happen.

Karen Volker:

I want you all to leave with a sense of hope, of possibility, and also of urgency. There’s a lot we can do to prevent this in the future, but let’s also focus on preventing and interrupting violence today, tonight, and tomorrow. Ideals are like the stars—we never reach them, but they guide our path.

Kitagawa then thanked all panelists and participants for contributing to the rich discussion, and invited all present to remember, in their own way, the victims of man’s inhumanity to man.

“We stand in solidarity alongside the survivors of Religicide, grateful for their tenacity and resilience pointing the way forward. Our survival as a people and a planet depend on it.”

– – –

JoAnne Wadsworth is a Communications Consultant for the G20 Interfaith Association and acting editor of the “Viewpoints” blog.