By Steven K. Moore, PhD.

– – –

A UNHCR Tasking

It was mid-winter and frigid in the mountainous Balkans in 1992. An official request had come to the Canadian contingent from the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR) to provide support for a small number of Muslim men, women and children (32) who had recently fled the Bosnian war that had crept its way to their town from points further south.

Having been denied entry into Croatia at the bridge crossing, they traversed the Sava River that separated the two countries by boat in the dead of night. They were now in Kostajnica, Croatia just across the border. Local authorities discovered them huddled in an open field, suitcases in hand, doing what they could to keep warm, surviving on what little food they were able to bring with them.

A New Year’s Eve Like No Other

Then-Major Bernd Horne of Bravo Company, who had just been tasked with providing support for the refugees, approached me following the Commander’s Orders Group saying, “Padre, we’ve got men, women and children…some elderly…some sick. We need everything we can get our hands on. Whatever you can do would be greatly appreciated.” I searched the camp and was able to commandeer three large boxes of clothing that had recently arrived and an additional carton of Christmas gifts from a Roman Catholic parish in Atlantic Canada marked for children: boy or girl. Once the items were loaded, I climbed into the truck and the small convoy of vehicles headed off to Kostajnica … a two-hour drive south toward the border. As a Canadian Armed Forces chaplain serving with the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) in the former Yugoslavia, this was to be my first brush with what the Western world would come to know as ethnic cleansing—a New Year’s Eve to be indelibly etched into my memory.

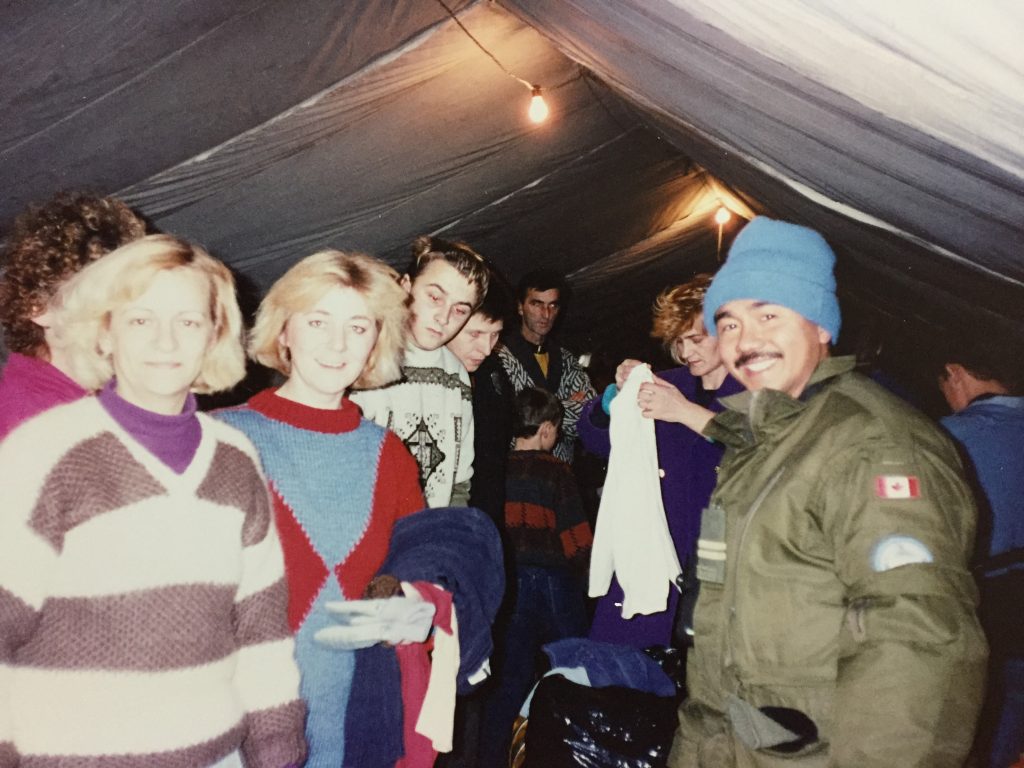

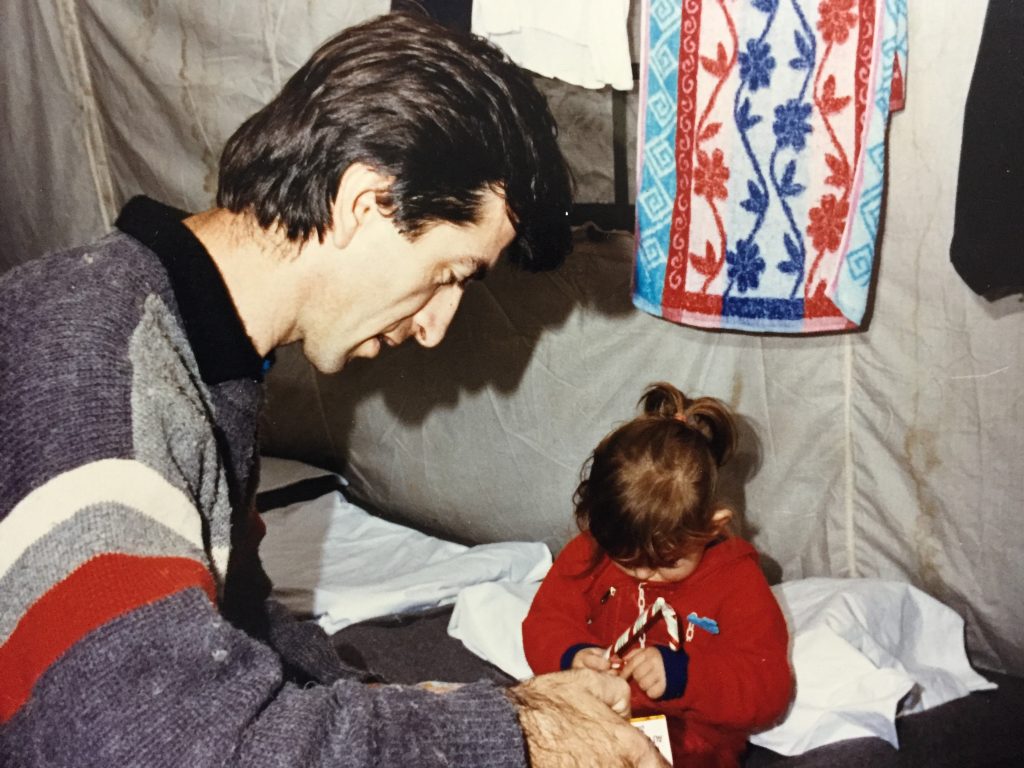

Once arriving at the Base Camp, the boxes were quickly unloaded and brought inside the modular tentage that served as shelter. Gas-fed heaters and generators labored noisily outside the tents, providing much-needed warmth and lights. Inside were cots, foam for mattresses, parka liners, blankets, Coleman stoves and lots of IMPs (individual meal packets – hard rations). The women sorted the clothing quickly, as they knew who needed what and how many. I recall one mother sobbing as she collected clothing for her children; arms were wrapped around her as others tried to console her. For some, leaving everything that they had ever known in exchange for an uncertain future was simply too much to bear. When the box of gifts was opened, the children excitedly began reaching inside for packages, pulling out whatever they could grasp—the older children making sure that the younger ones weren’t left out. The festive mood lifted everyone’s spirits, as the smiles and laughter of their children helped the adults to briefly forget present circumstances. There were candy canes, teddy bears, storybooks, racing cars and much more. No one mentioned Christmas – Christian or Muslim. In the giving and receiving on that New Year’s Eve in 1992, religious difference had all but disappeared. Transcending ethnicity and creed was the humanity of the other.

Edina’s Story

As the afternoon wore into evening, and having noticed an embroidered cross on my uniform, a couple in their early 30’s with two small children pulled me aside. In her halting English, over the next half hour, Edina pieced together the tortuous road leading to their collective decision to flee Bosnia—a Muslim minority in a predominately Serbian area.

Since the outbreak of hostilities, she found it especially troubling that friends from her youth had turned on her so easily simply because she was Muslim, something that in multi-ethnic Bosnia had never truly mattered before. The effects of the war became more evident as time wore on. Identity boundaries, once porous, had suddenly hardened quickly, with groups gravitating to their own as the identity need of security became increasingly pronounced.[1] Creeping alienation manifested initially with the family losing their jobs, as they had been out of work for an extended period of time. Soon their children were no longer welcome in the mainly Serbian schools. Parents banded together and started homeschooling, periodically changing location in an effort to conceal their whereabouts for fear of targeted mortar fire. To keep food on the table, they sold whatever belongings held monetary value and lived as frugally as humanly possible.

Lately, it had become increasingly difficult to purchase just about anything. The deciding factor in leaving was the continued shooting of Muslims at night. Under the cover of darkness, Serbian snipers had begun penetrating wooded areas near Muslim homes, and using the interior house lights to their advantage, they were firing on the unsuspecting occupants through un-curtained windows. Edina crouched low to the tent floor to demonstrate for me how at night she crawled from one room to the next in her own home out of fear of being shot. She was convinced that if they stayed much longer in Bosnia, they would all be killed.

A Refugee’s Reality

While I was still talking with Edina and her husband, the local UNHCR representative and a Russian military officer with the UN came into the tent. He gathered the refugees together and announced that due to their lack of proper documentation, the Croatian government had declined their request to resettle—difficult news to convey. The earlier light moments of sharing dissipated as a pall of gloom descended in the tent. The men grew silent and the women—not wanting to worry the children—tried to conceal their tears.

Edina turned to me and pleadingly asked what would happen to them and where they would go. With moist brown eyes and furrowed brow, she searched my face for some hint of hope. It felt as if she looked into my very soul when she asked me what I could do for them. I have never felt so inadequate and powerless before or since. With as much compassion as I could muster – knowing within myself there was little I could do for them politically – I nodded understandingly and told her I would try to help. I could make no promises to her. I’m afraid it wasn’t what she was hoping to hear. The last I heard, Edina, her family, and the other refugees were transferred to a refugee camp on the outskirts of Zagreb, Croatia’s capital.

An Urgent Need for Religious Literacy

Having lived among the people of war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, I bore witness to some of what tore at the fabric of their society. Sadly, co-opted religion exacerbated a situation already fraught with ethnic tensions. September’s Bologna Forum will focus on religion’s contribution in mitigating the onslaught of ubiquitous inter-communal conflict.

In today’s world, as witnessed in the Balkan conflict, concern exists for the persistent drift toward the sacralizing of violence toward the other—the religious justification for such acts invoked by certain of its leaders, regardless of creed.[2] In the former Yugoslavia, religious symbols became distinguishing insignia, worn by irreligious actors without any comprehension of their meaning. The dearth of religious literacy within communities of faith is undoubtedly among the contributing factors to ethno-religious hostilities—an egregious failing of spiritual leadership and cause for concern. In its absence, the faithful are far less able to navigate the complexities of ethnic conflict and far more vulnerable to the wiles of those who manufacture the false narratives that feed it.

[1] Vern Neufeld Redekop, From Violence to Blessing: How an Understanding of Deep-Rooted Conflict Can Open Paths to Reconciliation (Toronto, Canada: Novalis, 2002), 31-60.

[2] R. Scott Appleby, The Ambivalence of the Sacred: Religion, Violence and Reconciliation (Lanham, Maryland: 2000), 67-71.

– – –

S.K. (Steve) Moore, PhD has been a Padre in the Canadian Armed Forces for 22 years, with operational tours to Bosnia during the war (92-93), Haiti (97-98) and doctoral research in Kandahar, Afghanistan (2006). His post-doctoral work led to the chaplain operational capability, Religious Leader Engagement (RLE), now being integrated into military training. He has advanced RLE within NATO and the Commonwealth, increasingly assimilating a whole-of-government application—concepts now being adapted to the civilian sector. His publications include “Military Chaplains as Agents of Peace: Religious Leader Engagement in Conflict and Post-conflict Environments” (Rowman & Littlefield, 2013) and “Religious Leader Engagement as an Aspect of Irregular Warfare: the dénouement of a chaplain operational capability” (CANSOFCOM, 2020).